My therapist said my assignment for the week was to continue seeking gratitude. I think he sensed in me a yearning to make something of my pain. To plunge ever deeper into mourning, that I might discover something sacred within it.

"Consider what it would look like to get to a place where you can say 'I get to grieve,' instead of 'I have to grieve,'" he said.

"Oof, I don't know, man," I responded. "I'm definitely not there yet."

"Keep working on it."

And I will. I will never run from this grief. I would rather drown in grief than walk away from it if it means I get to spend more time with my daughter in memory. But I am still angry. I feel wounded and cosmically betrayed to be in this position.

Etta was just here. In my arms. I can feel her soft cheek against mine, her curious fingers wrapped around my pinky. I still turn around to look at her while I'm cooking in what had become our morning routine—her laying in her high chair and cooing as we made breakfast together for Mama.

To accept her loss means to concede a world without my daughter. And from the moment she was born, I understood that such a world was unlivable.

Recently, on a cool evening walk beneath pink clouds and the whisper of palm trees—the same walk we used to take with our daughter—my wife said to me, "It's like I spent a whole year creating this masterpiece, and I look away for a second, and she's destroyed." She sees me nodding, solemn and breathless. "Now we're just doing our best to pick up the pieces." I was rocked by her perfect description of the moment. Tears welled as I contemplated what was lost.

It reminded me of an experience long forgotten, walking the halls of DePaul University as an undergraduate. Within the Student Center, the nexus of the Lincoln Park Campus, was the Cultural Center. Nestled just inside the entry, the Cultural Center celebrated global cultures and traditions with interactive exhibits, inviting students to engage in whatever interested them: global food, art, guest speakers, music and so on.

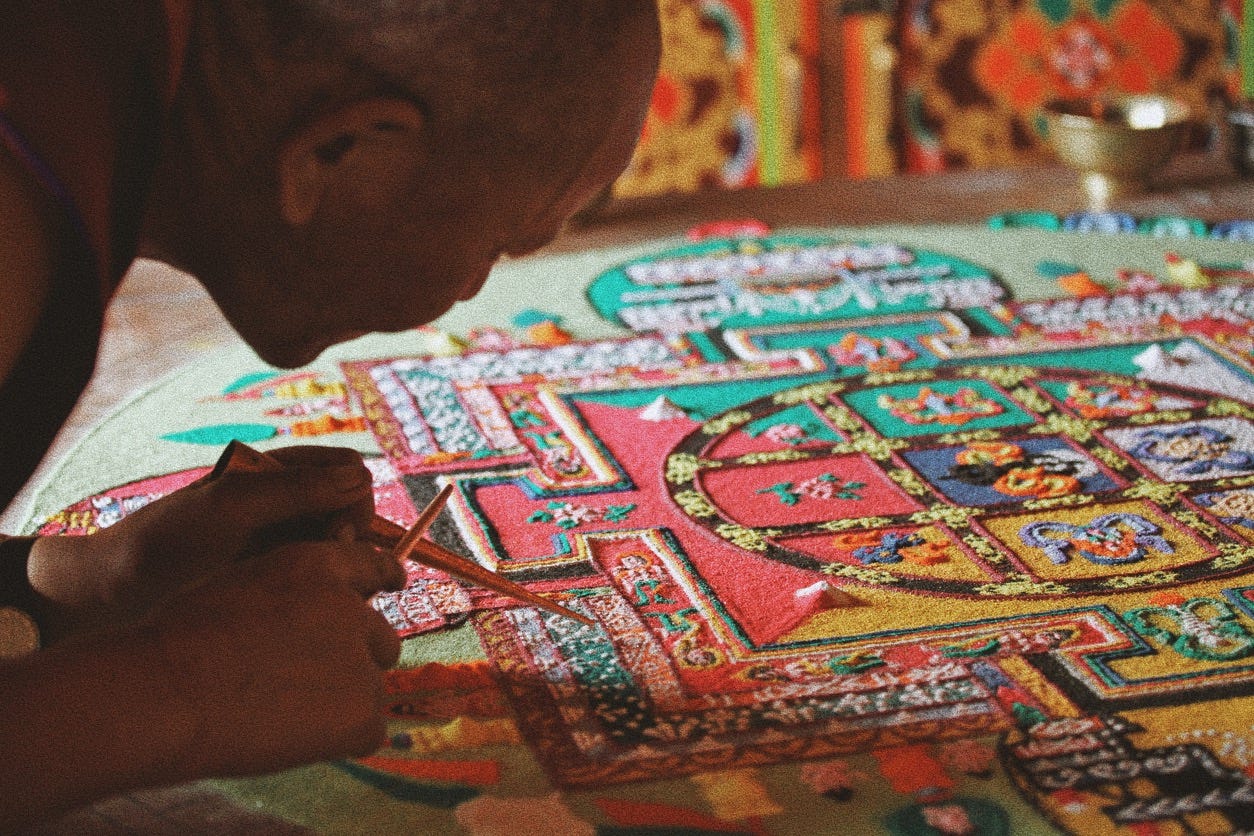

One day, inside the space four Tibetan monks clad in orange and red robes arrived, their close-cropped hair dark and stubbled. One of them wore glasses.

At their feet along the floor was a large, five foot wide, charcoal-colored slab, much like a chalkboard. At first, the monks used the tension from string dipped in chalk to snap intricate geometric patterns onto the slab. I had made several loops through the building to see the end result. By the end of the day, the monks were gone, and the office was closed. But behind the glass, I saw the detailed outlines of what I imagined would become a sand mandala. I had only ever seen images of them in art history classes on campus. I stood there for a while, staring down at the perfect circle, precise and masterful, filled with intricate white contours that laid the path for visual expressions of their faith, values, and cosmic ethos.

The next morning, the monks were back, tea in hand. There were small bowls of sand neatly lined along the floor in deeply saturated colors. Next to them was a bundle of large, pointed rods that resembled oversized chopsticks. I later learned they were chak-pur, hollow, funnel-like tubes used to filter the sand.

When I looped back later in the day, the monks’ work with the colored sand had begun. They sat on the floor, a couple with their legs crossed, a couple on their knees. They leaned over, chests parallel to the floor, chak-pur in hand. Every few minutes, they reached for a container of sand and carefully sifted some into the base of a chak-pur. They then turned the tube downward, pointing it towards the slab. They placed a second rod perpendicular to it and gently rubbed it back and forth against the notches of the chak-pur. The rubbing sent vibrations down the tube that slowly funneled the sand out with the precision of a pen. One funnel of sand at a time, they worked their way out from the center, drawing with sand.

For days, the monks continued like this, working almost eight hours a day. It had become the talk of the campus. I began rerouting my path across campus through the Student Center so that I had multiple chances to check in on the progress of the mandala. Every time I saw these men, they were calm, focused, patient. It was as if their life depended on the completion of the sand mandala. Hour after hour, day by day, the mandala came to life, each circle wider and more colorful than the last. Regularly, they'd break into Buddhist songs—stunning multiphonic melodies that reverberated through the hallways.

One week later, the mandala was completed. It was one of the most beautiful pieces of art I'd ever seen. A perfect masterpiece. Concentric circles, segmented by blocks of colors with intricate figures and forms that told ancient stories honoring Tibetan culture and values. I felt lucky to have witnessed its creation, astonished by the human capacity for the miraculous. The monks were speaking with curious students who approached them with questions. The energy around the Cultural Center was celebratory. The whole campus, which had slowly witnessed the creation of the mandala, was eager to share in its splendor.

I headed home for a long night of homework, excited to return again in the morning when there were fewer people around. I wanted to study the mandala more closely. But as I entered the Student Center the next day, it had disappeared. There was no trace of the monks or their colorful composition. Confused and dispirited, I asked the office where the mandala had gone. Had it been glued down and hung somewhere?

"They brushed it away," the woman at the front desk told me with a big smile. "We had a closing ceremony last night and they swept it all up. It's part of their tradition; it represents the impermanence of life."

I felt my heart oscillate between awe and heartbreak. How regretful to see something so magical gone so swiftly. I mourned the sand mandala and felt its sudden absence like a comforting hug brusquely cut short. I felt deprived of time, denied the chance to soak in the mandala's grandeur and the monks' hard work.

I couldn’t believe the masterpiece was swept away more quickly than it was created, and yet I remember feeling heartened by the monks’ confidence in and acceptance of transience. A quiet wisdom worth striving for, but one I understood I didn't yet have the maturity to claim.

With the benefit of hindsight, I now see that was one of my first lessons about grief.

Translated literally in Sanskrit (मण्डल) to "circle," sand mandalas have functioned since at least the 11th century as a sacred meditation ritual and spiritual reflection (source: Minneapolis Institute of Art).

The creation of a sand mandala is thought to gather spiritual energy, and they are regarded as a process of healing and purification. Its destruction, at the Dissolution Ceremony, returns that energy to the world. The sand is often bottled and physically returned to the Earth to be transformed again (and again and again).

For me, these teachings on impermanence reveal something about death. What a transformative idea that the creation of something ephemeral, even before its fleetingness has been revealed, is itself an act of healing and spiritual growth. We're taught to view death as an ending. But it could be a symbol for impermanence, a natural transition from one form of energy to another. Something is not beautiful because it lasts. It is beautiful because it existed at all.

This affirmation is direly needed in the face of my personal seismic dissolution. It takes all the energy I have not to succumb to rage and blinding depression. Most days, I lose the battle.

I struggle with the simplest of truths. That Etta is gone and she's not coming back. That I will never get to see her grow up, never hear her speak or see how thick the curls on her head will get. That we're only months into what will be a lifetime of grief, and those months have already felt like years. That our desired family will always feel like an incomplete puzzle with a piece lost to us forever. That to have a family means to start the process all over again. That at our age, there is no guarantee a family is even possible. Maybe that’s why Courtney and I chose terramation for our daughter rather than cremation. Even in death, we saw her body as full of life and promise, so we merged her remains with wildflowers to be transformed into nutrient-rich soil. Perhaps we sensed that new life was possible among the trees and the insects, even if it meant knowing her in a form vastly different than we'd hoped and imagined.

We may have already understood, somewhere deep in our ancestral being, that to exist, to live, is more than flesh and bone. Etta's death may have stripped us of the gifts of her touch and smell and sight, but it does not take away the ability to remember her or to feel her presence in all things. Her death does not devalue the journey that brought her into being. It strengthens it.

Every day in our child's development and birth, right up to the day our baby girl died, was like the creation of our mandala. We carefully and meticulously crafted her in the image we desired. We etched our values and laid bare our fears and insecurities. We breathed life into her being, just as monks breathe life into sand. Etta was the manifestation of all of our dreams until death wiped away her body like a brush to sand, and we returned her to the Earth. Though her absence fills the space between us with longing, she will always be our masterpiece.

As it turns out, I am grateful for my grief, in the sense that I get to practice the art of remembrance daily. And in so doing, my daughter‘s name and presence, even in death, have never been more alive.

Writing I’ve Enjoyed Lately:

by Alex Elle

A beautiful and necessary reminder about the presence of joy, even amidst the chaos.

“On Letting (Your Own) Art Revive You”

A gorgeous essay exploring disability, self-love and revival through the lens of art.

by Dishkitty

Because sometimes we just need a little dose of joy.

“Siri, Teach Me How To Grieve”

by Joél Leon

Important reflections on grief and the ways we “tuck ourselves away.”

“tending to the roots before the bloom”

On nurturing our own soils, “rich with lessons.” + some journal prompts.

Consider checking these folks out.

Thank you for reading.

Please consider subscribing.

More from Overture soon.

I continue to be in awe of how you express your grief and process in community. Your words bring me comfort as I process my own grief. I see you - you are held, and witnessed, and loved.

I remember the exact moment in time that the monks made the mandala in the student center - I was transfixed, too - and it's such an excellent lesson to keep pulling from. Thank you.

Another great read, Matthew. You captured the complexity of grief so beautifully.