Note: All words across varied timelines, characters, and perspectives are written by the author.

MATTHEW

April 2007

How is he still in that damn chair?

At the base of the stairs, home from a 14-hour day, I glance into the darkness as my father broods in the corner, the blue light from the TV reflecting his misery. I have already been to school and back, to work and back—yet there he sits, my decrepit father, in the same place he was when I left this morning. My sympathy for the man is waning; the catheter bag at his hip is no longer an excuse I wish to brandish. The man is lost, a guidepost for everything I don't want to be.

He hears my steps and looks over briefly, his eyes catching mine. But I don't nod, don't say anything. I look away, open my bedroom door, turn on the lamp atop my desk, and close the door behind me.

"Goodnight, Pops," I mumble to myself. He's not supposed to be here still.

My resentment has festered like a sore that refuses to heal. Mom and Pops have been spiraling toward divorce for a decade. They couldn't afford the legal costs, so they opted for separation. But they can't afford separate homes, so my father's apartment is triangulated to the 50-square-foot area between the basement chair, television and bathroom. It is meant to be temporary, but my father rarely has the will or capacity to initiate a solution.

None of us were prepared for his diagnosis. Blood and tiny black pellets in his urine were a sign of something dire. The prognosis was worse than we imagined. Stage 4 bladder cancer. A death sentence for many of his age and condition.

Pops was given two months to live; the only solutions were immediate chemotherapy or an exhaustive bladder replacement surgery. We proceeded with the latter—more dramatic, rapid and efficient, assuming it worked and that insurance would cover it. More unnerving, too. It was a blind experiment whereby they removed the existing bladder and built a new one using the large intestine, all within eight hours. But there's no way of comprehensively testing the viability of the organs before operation; one has to hope that each organ is operable and well-equipped to sustain the transformation.

They gave my father a 60% survival rate. "That's pretty good," his doctor said. That's a 40% chance of death, I thought. It was enough to make me confront God again—to sober me to the reality that, however fractured our relationship, I wasn't ready to let my Pops go.

And I didn't have to. Pops survived his procedure; it turned out his appendix was cancerous, too. They cleaned him up nicely, gave him a catheter, and he started his arduous journey back to normalcy.

But all that feels irrelevant now, a few months post-surgery. Empathy can be tested when it feels one-sided. And my father, despite beating cancer and having a successful operation, doesn't seem like he cares to live. He's taking it all for granted, consumed by self-pity in his corner chair. Despite the accumulation of my family's anger with him over the years, we seem to care more about his life than he does.

"Matt, you never come to see him," my sister Jessica said one evening while he was hospitalized. Apart from operation day, I had visited Pop’s bedside only once in at least a month. "I know."

Seems my father wasn't the only one shutting people out.

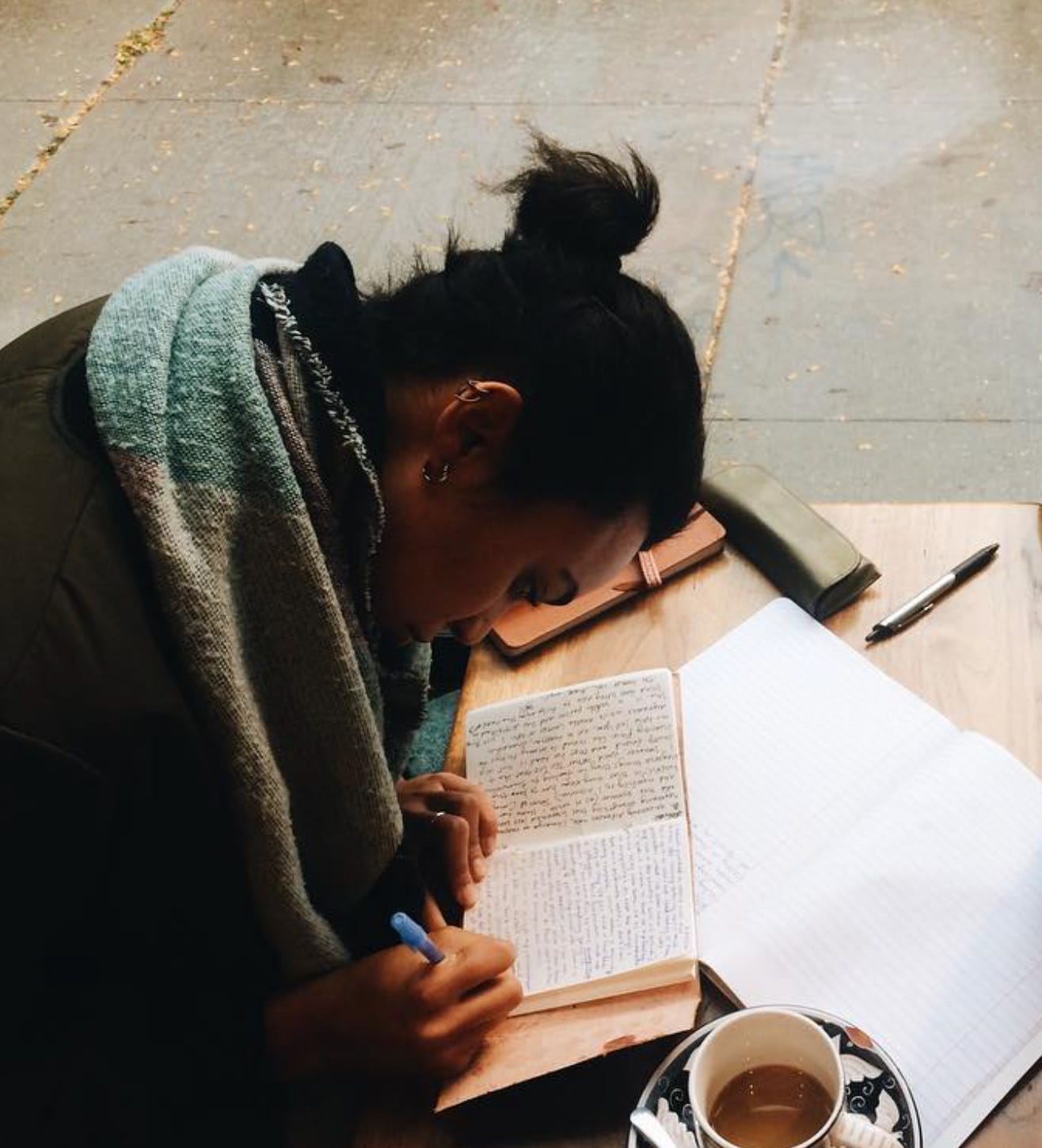

As I adjust to the light in the room, I throw my bookbag on the floor next to my bed, sit at my desk, and prepare for my third shift—homework. As is my routine, I put on my headphones and play moody classical music. The tones of melancholy piano chords and the swells of emotive synths drown out the noises in my head. My safe space.

Exhausted from fifteen hours of school and work, I struggle to open my drowsy eyes. Understanding these advanced textbooks is tricky enough with sufficient rest. Adrift somewhere between fatigue and delirium, my brainpower is insufficient for the task.

On the other side of the wall behind me, I hear Charlotte, my baby sister, creeping halfway down the steps, presumably to say goodnight to our father. She should be asleep already. Her visits to Pops are a nightly ritual, but not usually at this hour. She hurries back upstairs, but I know she'll be back. Her restless, wandering mind seeks comfort; I wish I had more to give—to anyone and anything.

A few minutes into my homework, I hear the door open behind me, as expected. I lift my headphones off the ear closest to the door and snap around quickly to acknowledge her.

Charlotte's head pokes past the door frame like a cartoon, her round head, nappy hair and doughy eyes as endearing as ever. She's 12 already, but I still see innocence every time I look at her and feel in her the youthfulness I've lost.

"Can I just sit here for a little bit, pleas—"

"Charlotte, no. I'm doing my homework. Go to sleep!"

With a wave, I signal her to close the door and turn around quickly, returning to my calming melodies. Shutting her out like this is breaking me, but I already feel on the verge of collapse. Any distraction, however small, might tip me over the edge.

I shake my head as I hear the door close slowly behind me. With deep, dejected breaths, my leaden head sinks into my arms, folded on the desk. I can feel the tears brimming. I hate being this person; I want nothing more than to hang out with my baby sister—to play video games, card games, or quip about all the curiosities she's gathered like collectibles. I call her "Curious George" for a reason. But I feel stuck; I don't know how to combat my fatigue and the sheer lack of time. My gut feels stretched beyond comfort, contorted by an ever-swelling anger.

I swing my arms and head back into the air as if to push out the emotion. As I peer up at the ceiling, my eyes catch the fluorescent light tile directly above my head. I keep the antiseptic office light off these days. I prefer the warm glow of my desk lamp, but mostly I want to mask the littering of fresh mouse poop that the light illuminates.

I have accepted my role as the eldest child and only brother and the responsibilities I assumed as my lot. I feel loved by my family for the financial and emotional support I offer, yet judged for how temperamental it's made me. My joy is gone, as is my levity and spontaneity. This corrosive feeling has been gnawing at me for years.

Ever since Pops got sick, I've done everything I can to support Momma. I don’t want to have to scrounge for nickels and dimes again in the couch cushions so that I can buy my sisters a Subway sandwich. Or use candlelight when the electricity goes out. Or bathe with pots and pans when the gas stove was our only heat source. Or do laundry on the stove, stirring our clothes clean with a wooden spatula.

Momma works hard, toiling odd hours and balancing several jobs simultaneously. But her three modest service jobs barely cover the bills for a family of five. It doesn't help that we're here in Southwest Minneapolis, a low-income family amidst affluence; everything's more expensive here.

I never questioned why I felt such a need to support my family. The truth is, nobody asked me to; I just got to work. As long as it means keeping the lights and heat on, I'll do what I must.

I hope Charlotte understands when she's older. I sped up my childhood for you, Sis, and your sister. So that maybe, one day, we can all escape this vicious cycle and be a family again.

Finally, after a few hours of homework, I call it a night. My brain went to bed over an hour ago. I must reserve my energy for when it all starts again tomorrow.

Before sleep, I tiptoe up the stairs through a dark house to check on my mother. I haven't seen her yet today; I barely see her awake anymore. Between her long hours and mine, we mostly trade nocturnal visits while the other sleeps.

I walk toward Momma's room. Her side table lamp is still on; her wine glass half empty. She's fast asleep, arched over on her pillows, snoring in the faint light. My exhaustion doesn't compare, and I know it.

I watch as she sleeps, my sympathies extending to her telepathically. Someday, I'll provide you with a life of ease, I think to myself. I inch toward the bed so I don't wake her, kiss her on the forehead and pull the blanket back over her before turning off the light. I'll be tucked in, too, by the time I wake up tomorrow. We look over each other in this way. Quietly ensuring each other's safety and warmth from the reaches of night.

"Goodnight, Momma."

On my way back downstairs, I glance across the dining room to Charlotte's bedroom door. I don’t see her lights on. Her anxious mind is finally safe under the cover of night. The thought comforts me.

Sleep tight, sister. I'm so sorry.

I check the locks one last time before retreating to my room. At last, my room goes dark.

I lay silently for several minutes, struggling to pacify the turmoil in my mind. I'm at war with myself. I've surrendered my youth for family—barely have time for friends, basketball or art. I've adopted the role of "protector", but who is protecting me? Where is my keeper? Where is my peace?

CHARLOTTE

April 2007

He feels like a ghost now. He doesn't talk anymore.

As I sneak up the stairs, I look back at Dad. He's half-asleep in the dark with a beer in his hand. I think he's watching Seinfeld reruns. It's like he lives in that chair now, but it was always his favorite. He doesn't look like himself—like my real dad is stuck inside. He's angrier than he used to be. Sometimes, I worry that he passed on whatever he's suffering from to me, like his dyslexia.

"Goodnight, Daddy," I say to him before I turn around and quickly hurry up the stairs. I still feel like monsters are trying to grab my feet in the dark. "Night, baby," Daddy mumbles back.

I feel anxious. It’s way past my bedtime, but I can't sleep.

I hate that my Dad got cancer. And that he argues with Mom so much. And that he's so sad all the time. But I like that he's still in the house. I know he's just a few steps away if I need him.

Upstairs, I tiptoe through the kitchen—I don't want to wake Mom. I can hear her snore from the hallway. I peek through the crack in her door before returning to my room. Her door is always a bit open because our house is on a slant. She's snoring, wearing a giant t-shirt. Her head rests against her pillows.

I hope her dreams are full of beauty and color. She deserves the whole world.

She tucked me in about an hour ago. I wonder what she'd say if she knew I was still up, wandering around the house. Even though she's tired, she always finds time to give me a goodnight kiss. I don't think she checks on Daddy as much anymore, though.

Mom fell asleep during our American Idol session again—I wish it didn't annoy me so much that she can't stay awake with me. I know she's tired and doing her best, but it feels like no one has time for me anymore. Daddy feels like a shadow. Mom is always working or too tired. Matthew never stops working. And Jessica is too busy becoming a teenager. What about me? What about their baby sister?

Maybe I can sit with Matthew for a while. He's always up.

I sneak down to the base of the stairs. Jessica's door, right after Matthew's, is dark. She's probably sleeping. But I can see the light under the door of Matthew's room, like usual. I open my brother's door slowly, almost like I don't want the light to escape.

"Can I just sit with you, Matt?" I whisper.

In a hoodie and headphones, my brother is hunched over his desk. He turns around quickly and lifts one side of his headphones off his ear.

I don't think he heard me. "Can I just sit here for a little bit, pleas—"

"Charlotte, no. I'm doing my homework. Go to sleep!" he jumps in before I can finish. He shoos me away with a swipe of his hand before turning back to his desk.

His words hurt. All I want is to sit on his bed while he works. I hope he knows how much I love him.

Ever since Daddy got sick, Matthew started working. I mean all the time. He goes to school all day, then drives to work to wash dishes and make sandwiches for rich people. I hate rich people. Then, he comes home late and stays up past midnight to finish his homework.

Everyone says how much Matthew does for us, but he's always so sad. He used to be so fun. He's a lot like Mom.

I slowly shut the door, hoping Matthew will turn around and change his mind before the door closes. I watch him shake his head like he’s mumbling to himself.

How did we get here? We don't talk. We're not happy. We don't spend time with each other. We're just tired and crabby, sneaking through a dark house and looking at each other through cracked doorways.

No one asks a lot of me; I’m just a kid. My job is basically to finish my vegetables at dinner and make the school bus on time every morning. But you grow up fast when life is a struggle, especially when it's a secret you have to keep from your friends. I'm growing up way too fast. I see all my friends spending time with their families; I spend more time with some of theirs than I do with mine. They take trips to beautiful, far-off places, host barbeques, and laugh with their neighbors.

I don't know if my friends would get what I'm going through. They don't know what it feels like to wonder when the heat comes back on. This may be the way it is for us now.

I don't know what else to do, so I finally go to bed. I hold my American Girl doll, Linny, her arms hanging from their threads. I've had her since I was four when we first came to America from Sweden. I still hold her small brown body close when Mom and Dad get angry and yell at each other.

I wish they knew that even though I’m young, I want to help. I want us to get through this together.

I turn off my light and lay my head on my pillow, looking into the dark driveway next to our house. My room is on the same side of the house as Matthew's, downstairs. I can see the light in his window shining against our neighbor's house at night. As always, it's still shining bright.

I picture my brother in his room, working away to his music. As I stare at the glow from his window, I see myself next to him, sitting on his bed and keeping myself busy until his work is done. I want him to know that he has someone looking over him the way he looks over us.

I lay there for a couple of hours, daydreaming. My brother doesn't seem to move.

Finally, I see shadows moving in the light coming from Matthew's room. When he gets ready for bed, he always makes his way upstairs first, maybe to clear his dishes in the kitchen. I hear the creaks from his slow steps moving around in the dark. For a moment, he gets close to my door. But after a few minutes, he turns around and returns downstairs.

He's in his room again. I think he's finally going to bed. The light in his window goes out. I don't know the time, but I am happy knowing my big brother is going to sleep. I am comforted knowing I am the last person to see his light go off. For now, my family is resting.

Tomorrow, we'll do it all again. But for a few hours in this dark, I feel okay.

I love you, brother. Sleep tight.

MATTHEW

December 2013

One chilly night, alone in my South Minneapolis apartment, I received an email from my baby sister Charlotte. In the email was a link to a couple of pages of writing and a message that said, "I just kind of started writing."

That winter was heavy for two reasons. It was particularly bitter, a cold so biting it burst pipes all over the city. But it was also the first season in years that left me immobilized by the depression that once tried to end me. A depression I thought I’d overcome. It was my first year back in Minneapolis after graduation; I felt isolated, alone and unsure of my path.

Charlotte was away at school in Chicago, where I'd just spent four years. And her words, seemingly out of the blue, made me feel less alone. They were from a short essay for her memoir class; Charlotte was into writing now like I was, and like so many of our relatives—mostly ministers.

Line by line, Charlotte recalls the memory as a fixture of her childhood.

"I should have never asked so many times before pulling my brother's doorknob towards my chest. I was fully aware of my role as the annoying little sister, but I so badly wanted to keep him company. My repetition in yearning to sit on his bed and pester him for answers on every question in my little brain only furthered his frustration in having to stay up later than everyone in the house."

Time and time again, I rejected her.

And yet, she maintained her optimism, centered her compassion.

"But my brother, being the selfless human he was, disregarded all that for the sake of caring and providing. Two things I felt I could never say about my actual father. More shifts meant more money, and that was enough of a reason for my brother, if it meant less eviction notices for my mother. There he sat, frustrated with himself, in trying to provide for his sisters at 16, and there I stood, restless for conversation and awake at an ungodly hour for my age."

Almost a decade later, every word feels like a hug. She lets me know that she doesn’t blame me for the way I pushed her and Jessica away. Charlotte tells me, through tender reflection nearly a decade later, that she saw me and understood what I was going through. These affirmations away years of bitterness I'd harbored for the world. All most people want is to know that they are seen, loved and deeply cared for. I didn't realize how much I needed my sister's words until I read them. It was as if I was peering down at myself from the future, extending the warm embrace upon my back I desperately needed.

Charlotte's words were visceral, like the overdue stitching of a neglected wound. The bittersweet recollections of our childhood put me back in that sullen time loop. But her vantage point, a nest of still unprocessed perspectives, showed me a reflection of our youth I'd never seen before.

She inverted my adolescence in a few pages of text and expanded my world beyond aging traumas.

For years, I'd done for others but thought myself alone. I accepted my fate as the lonely, depressed teenager who sacrificed his adolescence for familial stability. In part, I depended on it. But in the embrace of darkness, Charlotte—the runt of the litter—was the family's secret watcher and protector, looking after us. I was never alone, after all.

MATTHEW

October 2023

I had far more privileges in my youth than my naïveté let me accept. I’m no longer able to look back on my life without the clarity of hindsight and all the privileges I took for granted. I empathize better now with all that others were going through within the same walls and time. This is a gift for which I am grateful and for which I owe Charlotte a debt of thanks. Woe is no longer me.

It is only now, in my most tender phase, that I'm able to reimagine my youth through a different lens. I wish I could tell younger Matthew to close the textbooks for a moment.

You will be okay, Matthew. Turn around. Acknowledge your sister—banter with her into the blue night.

Make sure that she knows she is loved. Make sure she feels seen. Make sure she grows up knowing that she is not a burden, a distraction, or an irritant.

And please, let her love you, too. Let her show you that you, too, are valued and seen. That you were never alone and never will be

This is all easy to say now. I don't blame myself for doing then what I felt was necessary to survive. Nor lacking the empathy at age 16 that I have at 32.

However, I feel the urgency to comb through my history—every forgotten intersection—and consider other perspectives. To extend grace to Pops, for not one of us understands the depths of pain he endured. To nurture the insecure, youthful parts in us all, who never felt loved and protected the way we red.

I feel urgency to remind myself more often to pause and breathe. To avoid getting so worked up about what I'm supposed to do I forget who I am or why I do it.

Charlotte's words remind me to cherish every moment I have with family, friends, and loved ones—to strive to be more present more often, beginning with myself.

When times are tough, and the world is especially dark, I remember to look up and trust that I am not alone. I remember to search for the light in the window.